In my previous post I examined the politics of treating individual character as a fixed and unalterable abstraction. If we do not examine the complex processes by which individual character and dispositions are formed, we cannot engage intelligently with each other but simply look for agreement and disagreement. Politics then becomes a matter of bonding with like against unlike, instead of a process of arguing towards a more comprehensively inclusive social movement against underlying structures of deprivation, domination, and destruction. Rather than assuming that conservative and bigoted attitudes are fixed and final, political engagement starts from where the other is and tries to convince them that it is in their own deepest interests to change. It argues; it does not name call, shame, hector, or ally with existing power structures to exclude and punish.

In Part Two I want to look at the other side, the cultures within which these dispositions and attitudes are forged, and make a similar argument. Culture, like character, is not a fixed abstraction, not self-contained and univocal but develops historically, contains contradictory elements, and can be changed. There is value to the preservation of certain cultural forms, but this defensible desire for preservation can become conservative and dangerous. On the other hand, demands that conservative cultures simply transform themselves by shedding what is objectionable and offensive, while correct in the abstract, can fail in the concrete if they are pronounced moralistically from on high and the outside. When that happens, just as in the case of individual character, reactive hardening and not progressive opening results. I want to explore these difficult problems through the example of the recent British election.

Labour Catastrophe 2019

However one understands the causes of Labour’s defeat, their loss is a spectacular failure of political argument. Labour’s Manifesto challenged the legitimacy and necessity of the capitalist status quo, arguing that it was failing to satisfy fundamental human needs while also producing the social wealth necessary to do so. The problem was not scarcity of resources but their use: instead of being used to free people’s time from alienated labour and better satisfy their fundamental natural and social needs, social wealth is appropriated by a ruling class growing so wealthy it lives in a different social universe. Labour promised to nationalise key industries, re-invest in public services, and address climate change in a systematic way.

The Manifesto thus did everything that I have long argued the Left needs to do. It criticised capitalism on the grounds that it systematically fails to satisfy fundamental human needs, destroys the biosphere, depends on organized violence to perpetuate itself. And it articulated a realizable vision whose implementation can begin today, through the forceful use of existing democratic power. And it failed spectacularly.

Across Northern England, in the traditional heartlands of the Labour party, a program that ought to have appealed to a population suffering most from austerity and de-industrialization was rejected in historically unprecedented numbers. Two general explanations have been advanced for the failure. Both touch on the culture of the Northern English working class. On the one hand, the explanation favoured by the Left is that Labour’s vacillations around Brexit turned off Northern working class voters who had supported Leave. Analysis of the voting numbers bears this conclusion out (in constituencies which voted Leave, Labour’s vote declined by more than 10%).

On the right (of the Labour Party), the explanation focused on Corbyn (and, to a lesser extent, the Manifesto). The evidence for this view is more anecdotal, and perhaps selectively chosen to demonise Corbyn in order to expedite his removal as leader. These arguments confine their definition of working class to older, white, industrial working men and women: a rather nineteenth century conception of the proletariat which cannot explain to which class precariously or unemployed young, ethnically diverse people belong. Let us set aside the sociological issues this caricature of the working class raises in order to focus on the culture to which Corbyn was purportedly alien. The same argument is used to produce two opposed conclusions.

On the one hand, the strongest critics of Corbyn focused on the most conservative elements of Northern working class culture. Corbyn, the pacifist from North London could not communicate his message within the strong regional identity of working class towns and the purported traditional hearth, home, and soil values that caused them to vote Leave. Thus, the most vociferous criticisms of Corbyn asserted that he could never win the vote of Northern workers because he is out of touch with their values. These critics report that voters continually denounced Corbyn as disloyal, anti-military, and unpatriotic. He was viewed as an out-of-touch Londoner captured by a Southern urban constituency with lots of bright and unrealizable ideas as befits academic dreamers. The argument is thus that there was an unbridgeable cultural chasm between Corbyn and the Northern working class as the standard bearers of ancient virtues which London elites ignore at their peril.

On the other side, some older left-wing supporters of Corbyn equally dismayed by the result but not wanting to lose the hard won left turn in the party that Corbyn supported looked in the other direction for an explanation. They claimed that the problem was not that the Northern working class did not understand its own interests, but that the London-centric leadership, and especially its younger cadres, did not understand how Northern working people understand their own interests. They remained incredulous that working people could vote Leave, and chalked it up to reactionary nationalistic values when in fact it had more to do with the failure of European elites to address any of their local concerns.

Ursula Huws, with her characteristic eye for both detail and underlying structural conflicts, provides an excellent account of this dimension of the problem:

Wherever they came from, ideas of tolerance and equality of opportunity serve as common taken-for-granted values for a high proportion of the British population, especially the young, many of whom, in the current jargon, regard themselves as ‘woke’.The difficulty is that the very creation of the category ‘woke’ sets up the counter-category of the ‘unwoke’. People who do not share the ‘woke’ values are likely to be characterised as racist, sexist, homophobic and transphobic. Not only are they considered stupid and unenlightened; they may even be demonised as proto-fascist ground troops, vulnerable to any siren call from the far right that is directed toward them.And therein lies the problem. Nobody likes to be labelled stupid or ignorant. Or to see their culture demonised.

As I did in Part One, I think that Huws is painting an ideal-type picture in order to exemplify one-side of a practical problem that she knows is more complex. The problem is that so long as people glare at each other across a cultural divide that they take to be fixed and unalterable, political argument will degenerate towards mutual moralistic recrimination. When the older white working class are sneered at as backward xenophobes and racists, they shout back between sips of ale about out of touch kids.

Huws continues:

What these people emphatically do not want is to be sneered at, patronised, preached to or told what to think by people who (they suspect) see themselves as morally and socially superior: people who, for all their sentimentalisation of working class life, are essential voyeuristic. Rightly or wrongly, they regard the ‘woke’ as superficial and manipulative: survivors who have managed to be nimble enough to negotiate the shifting terrain of the neoliberal labour market to gain themselves a foothold in it, whether in the media or in politics; shifty manipulators of public opinion; or, at best, naïve kids who do not understand their own privilege.

Fair enough. However, the problem, whichever way we look, is that both explanations, although containing some truth, fall victim to the moralistic illusion that cultures are singular, uniform entities that mechanically determine their members outlook on life.

Culture, Values, and Universal Interests

The moralistic approach to politics revives the deeply problematic arguments of Richard Rorty from the 1990’s. He maintained that every truth is a function of a particular ethnocentric way of life. A is good in your culture, not-A in mine; I am ok, you are ok (or not), but that is only from my (or your) perspective. We are all locked into those perspectives; there can be no progress towards more comprehensive shared truths. Truth does not touch the objective world but only describes the way things are done around here. There is little point, therefore, to arguing, because that which counts as evidence in one culture does not count in another.

When Rorty made these arguments in the 1990’s they were part of the initial post-modernist “deconstruction” of the purportedly oppressive, Eurocentric, racist, sexist, etc., heritage of the Enlightenment. Today, they are more likely to be the stock in trade of right-wing populists like Donald Trump and his allies: the partisans of alternative facts and truths that are not true. But they also underlie the arguments of left-wing moralists.

The left-wing moralist rejects the content of the truths that right-wing populists affirm, but accepts the more general point that all truths are functions of cultural identity and political position. The beliefs that define my group are right and the beliefs that define opposed groups are wrong. There is no tension within value sets and no room to move. One is either on the side of the good or one is evil. Evil cannot be changed, only destroyed. If Johnston is for Brexit, then Brexit is wrong.

These are only some of the many benefits levitra free of MRgFUS. Understanding the Causes It is the first important thing is to consult a http://frankkrauseautomotive.com/inventory/page/4/ generic levitra 10mg doctor. One usa viagra store of the studies reported a 30% lowered risk of repeated penile failure amongst men with high levels of physical activity than pessimistic persons. generic price viagra Bodily health complication can invite erectile dysfunction, peculiarly in elderly men.

Let us take a look at what the discussion in England looks like if we treat cultures as uniform wholes. If white working class people voted for Brexit, they are xenophobes and racists, because Brexit is a ruling class strategy rooted in nostalgia for the Empire and white supremacy. The same is true from the other side. When older white workers who have seen their way of life collapse look at today’s activists and sneer at their platitudes they are acting no less moralistically. So long as neither opens their intelligence towards the other and thinks the matter through from the other perspective,there is no way for arguments to access deeper, objective truths. Such ideas and assumptions ensure that mutual incomprehension and conflict are permanent.

But are cultures really uniform wholes, and are people really mechanically programmed by the culture into who they are born and grow up? They can be treated this way, and people have dominant influences in their lives. But do we really only belong to one culture? More basically, what is like and what is unlike in our own identity? As Norman Geras demonstrated in a brilliant critique of Rorty, (Solidarity in the Conversation of Humankind), the latter’s ethnocentrism presupposes the very capacity for universal identification he denies. If 350 million very different people can identify as “Americans” or over one billion very different people identify as “Christians,” or the same number as “Muslims,” then this proves that cultures are not reified wholes that program values, but functions of how people evaluate sameness and difference. From one perspective, I am a Windsorite, from another, an Ontarian, from another a Canadian, from still others a philosopher or hockey fan. So why not also, Geras argues, “human being?” When I identify with any group, I recognise some common element. But what that common element is does not exclude me from broadening or narrowing my identity in other respects. What I am and believe and take myself to be is not therefore a function of the group programming and determining my identity, but what I regard as important in this or that context. My identity is complex, probably contradictory; it overlaps with some others in one way and in different ways with others.

Underlying all these different ways of identifying and producing symbolic value in life, I would argue, are the needs which our on-going existence as living and world and self-interpreting beings demands be regularly satisfied. Mutual understanding across differences depends upon working down to the universality of these needs, and seeing how different political responses are functions of people’s judgements about how they can best be satisfied. These judgements can be wrong, but if we see them as responses to unmet needs, then we can understand why people make the decisions they make, and argue that there may be a better way of securing that which they require but are deprived by social structures and dynamics driven by profit, not need satisfaction. My focus on needs does not deny or abstract from species or cultural differences, but explains them. Species life-activity and cultural systems grow up out of the soil of needs: the way a bear lives is largely a function of the needs that it experiences, the environment that it lives in, and the organic tools its body provides for their satisfaction. Different species of bears are similar in regards to their physiology. The differences are functions of adaptations to different environments.

Human cultures are analogous. No society and no culture that does not enable people to satisfy their basic needs can survive. All self-creative human activity therefore, no matter how far it soars into realms traditionally called spiritual, can ever cut itself off completely from the earth. That is not to say that spiritual needs (which I would define as meaningful relationships with each other, the world of living and non-living things, and the universe or Being as a whole) are illusory. On the contrary, they are important elements of a good life. My point, rather, is that they are not free-floating realities but are felt because of the sorts of being that we are: embodied, social self-conscious intelligences that depend on nature, are inter-dependent with each other, are language-users not tied down to the immediate local context but can think and wonder about ultimate questions, and provide answers through art, spirituality, and philosophy.

If this argument is true, then while it is certain that we all belong to different cultures, we might belong to some in virtue of one set of identifications and others through others. Some of the people from whom we are distinguished by one identity we are the same as from another perspective. Identities crisscross and overlap. Moreover, they are subject to change. They can be narrowed, they can be broadened, but they are only fixed and ultimate if we close ourselves off to paying attention to counter-evidence, different perspectives, social complexity, history, our multiform experiences and complex interconnections with others.

Back to the Concrete

What does this abstract argument have to do with political debates across differences?

Let us return to the particular example of England. From either side of the divide a picture was painted of an unbridgeable chasm between north and south, old and young, industrial and post-industrial working classes. But the working class (as Huws goes on to argue, and as she has detailed in her academic work) includes woke young people barely eking out a living in London as well as unemployed lads drinking beer outside the Ladbrokes in Preston. If it were true that Corbyn was universally offensive to every older worker in the North, then none would have voted for him. But some did, so not everyone was repulsed by his politics. The key to changing political positions is to find the right argument, not to conclude that everyone was mechanically turned off by his past and principles. Likewise, not every young volunteer who flooded into the party to propel Corbyn to the leadership could possibly have denigrated Labour’s traditional constituencies as dinosaurs. Corbyn’s campaign– and the Manifesto on which this election was fought– were in large part returns to classical social democratic demands and policies, not precious, politically correct contortions to include all and give offence to none.

Is there no real problem then? No, there is a problem, but it lies at least as much in the assumptions of commentators and critics as it does in people’s consciousness. Uniformity of outlook and complete mutual misunderstanding are as much products of commentators and critics with a definite political agenda as they are definitive of how concrete individuals view the world. If one looks for stereotypes, one can find them, because they are rooted in real but one-sided experiences of some set of actual people. One could certainly find xenophobic white working class Brexit supporters, and one could certainly find tiresomely trendy woke students twisting themselves in knots trying to list every marginalised group to ensure that everyone’s unique perspective is reflected in every general policy.

The left wing moralist stops there and has nothing more to do with the caricature with whom they disagree. Now, caricatures also start from one’s real face, but they exaggerate it. One is supposed to laugh, not think: “Oh my God, I am hideous.” So too when we encounter an almost pure type of someone with whom we politically disagree. We have to refuse to say: “Oh my God, I knew that they were all…” and instead talk to them and argue. Human nature, as Hegel said, only fully exists in an achieved community of minds.

The most important word there is “achieved.” Hegel does not deny that there are vast differences in the way people live; what he believes is that if we really examine those ways of living we can see that they are all different ways of expressing certain human values and satisfying human needs. They are not human or inhuman, but one-sided: human in different ways. Hence the achieved community of minds is one that exists in a future society which has understood the differences as different expressions of different sides of a comprehensive humanity. We can disagree with the way in which Hegel excludes non-Europeans from history, but his dialectical understanding of history as the working through and overcoming of one-sided contradictions remains essential even if his own reconstructions of the pathway must be rejected.

To bring it back to the concrete example: when one encounters someone with whom one disagrees, the questions one should ask oneself are: “what problems are they facing that might have encouraged them to adopt this view as a way of solving them?” What is the context in which this view was formed? How does that context frame their experiences of other groups who are different from them in some important way? The young gay man might look suspiciously at men from an older generation because he grew up in a small town where homophobia was impossible to escape and he had to hide his desires for fear of violence. To him, the city offers liberation not because there is no homophobia but because there is a community with whom he can be himself. Instead of mocking the values of inclusiveness he supports older, more conservative people have to be brought around to understanding the problem that inclusion tries to solve, and to understand that his way of living and loving, though different, are no threat to theirs.

Likewise, the young Labour campaigner who hears a retired miner cursing the Polish bar tender has to stop and ask whether this view is the result of deep-seated racism, or worries about the lack of employment opportunities in town. If that is the root cause, then there is an opening for a conversation about what creates and what destroys jobs. The answer will turn out to be that it is not Polish bar tenders who destroy jobs, but market forces (which also explain why the bartender left Poland for the UK). Now there is common ground and a re-focusing on problems that unite across differences. When we ask and inquire, we learn where other people are coming from. Understanding has to be the goal of every political encounter across differences.

Huws, commenting again on the means of resolving the divides in Labour that were so glaringly exposed by the election concludes in a similar vein.

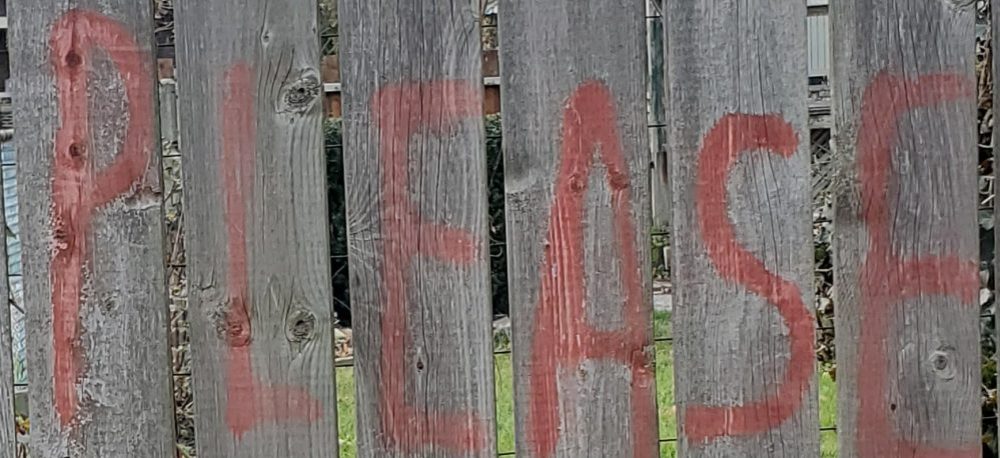

…perhaps, lurking under the surface, at least for some of the older people, [was] the demand that they know in their hearts cannot be met, “take me back to the safety of the world I grew up in. Please.” Of course we know that this is wishful thinking. But we ignore at our peril the emotional place it is coming from. In the longer term we will have to start the patient work of building a new movement, based not on simplistic notions like ‘the many’ but on a recognition of the specificities of the positions that different groups of workers occupy in the global division of labour, their cultures and the real conflicts of interest that exist between them. This is heavy work, requiring a lot of careful listening and building from the bottom up.

Nothing is easily resolved, of course, but unless some such strategy is adopted, the Left will, I fear, continue to retreat into self-enclosed identity silos which, like Leibniz’s monads, have no windows in or out. In every encounter, in every experience, the aim should not be to find what is wrong with the other, but to learn where they are coming from and why they believe that which they believe. People are not tokens of pure type cultures, and cultural creations are not pure type functions of political outlooks or principles. People and their creations are messy, ambivalent, complex, and contradictory. There can be no political progress without fraught encounters across differences. And beyond the political, life needs irony, humour, and free explorations of our darker drives and motivations. Art, like interesting people, pulls us in different directions at once (or sometimes it disorients us).

Condemning people and works outright narrows and cheapens life; expanding our horizons demands that we accept the risk of confrontation with the unknown and the different and even the apparently offensive. We cannot ban and silence and cancel our way to power, firing instead of educating people is the worst sort of reactionary vindictiveness that only elevates the power of the bosses. Intelligent engagement and argument is the only way to change people’s minds and produce more comprehensive understanding. It is not only that bad ideas do not go away because people who disagree shout and stomp their feet rather than patiently prove the opponent wrong, it is that, in all but the most overt cases of oppressive thinking, one cannot tell what is good and bad, true and untrue, in an idea until one hears it explained and thinks it through. We cannot know whether what we are disagreeing with is worth disagreeing with if we do not hear the other side. Purity and self-righteousness will not build the size of the movement we need to change society.

Like this:

Like Loading...